Paris Under Water: How the City of Light Survived the Great Flood of 1910

“a tight, concentrated tale of adversity and survival — of the ravages the untamed waters wrought and of the citizens’ courageous efforts to save their city (and themselves) from ruin…. At once pragmatic and inspiring…” —New York Times

At the turn of the twentieth century, Parisians believed they lived in the greatest city in the world. But Paris came to a halt in January 1910 when the river that provided much of the city’s life quickly became an instrument of destruction. Following weeks of torrential rainfall, the Seine overflowed its banks flooding thousands of homes and sending hundreds of thousands of people fleeing for safety and higher ground. This most modern of cities seemed to have lost its battle with the elements. But in the midst of the disaster, despite decades of political division, scandal, and deep tensions between social classes, Parisians rallied to help one another and rebuild. Leaders and people answered the call to action in the city’s hour of need. This newfound ability to work together proved crucial just four years later when France was plunged into the depths of World War I. What emerged from the waters, and from the war, was the Paris we know today.

“[This] riveting account of the great flood of 1910 and the city's benevolent response is fascinating and inspiring. . . . surprisingly gripping.” —Minneapolis Star Tribune

“It’s hard to imagine a more thoroughly researched history of the Paris flood of 1910. A truly first-rate book.” —Douglas Brinkley, author of The Great Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans, and the Gulf Coast

“Paris Under Water is a riveting account of a natural catastrophe that struck Paris in 1910. Going far beyond the boundaries of environmental or urban history, it draws on an exceptionally wide array of sources to offer the reader a meticulous, yet rich and personal, reconstruction of what the great flood felt like to contemporaries…. Jackson has succeeded masterfully in telling a fascinating story in a way that any reader will find utterly irresistible…. A tour de force of scholarship and brilliantly creative craftsmanship.” —Michael D. Bess, author of The Light Green Society

About the Book

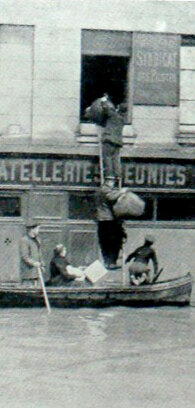

Nervous Parisians watching the water rise, January 1910

The ancient river Seine running through the heart of Paris has brought life to the city for centuries. Nearly every winter, it rises as water flows downstream from the mountains in central France and through its many tributaries. Just after New Year’s Day 1910, the water began climbing up the quay walls as usual. By the middle of January, Parisians knew the river would flood, but few suspected what was about to happen to their city.

Two American eyewitnesses who left Paris on January 21 heading home to the United States reported the casual way in which Parisians observed the engineers shoring up the stone walls which separated the river from the city. US judge Paul Linebarger: “They watched with an idle sort of interest that showed they had no idea that the overflow of the river would be so great as it has turned out to be.” Mrs. M.L. Nuttall: “As a matter of fact, the concern of the people was so slight that many of them appeared to treat the activities of the government engineers in strengthening the river banks as something like a joke.”

But the winter of 1909-10 was wetter than normal. Heavy rains and melting snow had engorged the soil, and a low pressure system stalled across the English Channel bringing more storms. The previous summer had been particularly rainy raising the water table higher than at any time in recent memory. When Parisians woke up on January 22, they realized just how far the Seine had shot up. An enormous volume of water was pulsing through the network of underground tunnels--subway conduits, sewer channels, wells, reservoirs, a labyrinth of old quarries from which men had carried stones in previous centuries to build the above-ground city, and basements and crypts dating back to Roman times. The swell of water grew hour by hour as runoff from the streets roared beneath the city, pushing into every nook and cranny. To everyone’s surprise, the water was not coming over the high quay walls, but under them.

The Zouave statue on the Pont de l’Alma

When Parisians wanted to know the height of the river, they closely watched the statues of four soldiers on the Pont de l’Alma. One of them was a Zouave, a proud colonial soldier in uniform with his cape flowing behind him, holding his rifle by its barrel tip. He stuck one foot forward as he stared watchfully across the Seine, his bearded chin pointing upward, as if poised to spring to action. When the water began climbing in earnest, the water was lapping against the ankles of his boots, about six feet above its usual level. But the quay walls through the city’s center were much higher, reaching well over his head. Once the water peaked on January 28 at 20 feet above normal, the Zouave and his fellow soldiers were up to their necks. Some of the debris sweeping through the city on the river’s powerful current included casks of wine and pieces of furniture, which Parisians saw as free for the taking. Risking life and limb, people leaned or climbed over the rails of the bridges to get as close as they could. Treasure-seekers tried to grab some of the river’s loot with poles or sometimes with bare hands, although the Seine swept most of the pieces away.

The Pont de l’Alma

The Parisian daily paper Le Matin described the frightful scene: “Planks, boxes, barrels, beams, debris from barges, tree trunks come at an indescribable speed shattering against the bridge supports.” The occasional loud crashes could already be heard far from the banks, like small explosions echoing through the city.

Writer Emile Chartier, better known as Alain, noted in his journal: “Gusts of wind blew the rain against the windows, and even though the window was closed, there was the smell of rain, as if the window had been left open.”

Soldiers and sailors from across France quickly mobilized and went to Paris where they joined forces with local police and firefighters. These first responders launched search and rescue missions throughout the flooded zone. The square in front of the Notre Dame cathedral became a launching point for boats into the still rising Seine. The Seine flowed much faster than usual reaching speeds of approximately 25 miles per hour. Its color changed to a murky yellow and its surface became frothy. Parisians could watch the powerful, swirling eddies.

Men patrolled the streets on foot and by boat listening for shouts and cries for help. When they found someone in distress, they plucked people from the rising water or from upper story windows. Some refused to be evacuated, and authorities brought food and water when possible to those who remained trapped on the upper floors of their homes.

Once prized pieces of furniture that people had worked so hard to buy and took great care to polish and clean were turned into muddy walkways they used to climb into boats. A widow suddenly realized that she had left behind an old cardboard box filled with money, and firemen rescuing her rowed her home to retrieve her life savings. One observer found a family of six who had gone for three days without food, “forgotten by accident, too poor to have provisions put by, too cast down to make noise enough to bring help.” An elderly concierge “sickened and died” while her building flooded, “and her dead body had to be carried out by a sailor on his back to a funeral by boat. Doctors could not get to their patients; babies were born in humble flats, and no help could reach the mothers for twenty-four hours.”

From Le Petit Journal Illustré

Those who did not witness rescues in person could see them depicted in the mass press. The images that appeared in numerous publications started to give Parisians a sense of the scope and scale of what was happening around their city. The illustration on the back cover of Le Petit Journal Illustré offered viewers a particularly dramatic scene emphasizing the work of rescue. Although it probably depicts a fictional occurrence, it captured much of the hope and fear of the moment. In this figure, rescuers have pulled their boat up to a house in the middle of the night and are gently lifting an elderly paralytic through his bedroom window to safety as snow whips all around. In the corner of the image, the top of a lamppost sticks up just above the level of the raging water, showing just how deep it had become. In the boat, a group of refugees huddle together under wraps along with some of their belongings, a dog, and a bird in its cage. They appear to have lost everything else--but at least the misery is shared.

Messina, Italy after the 1909 earthquake

Paris after the 1910 flood

In December 1908, southern Italy had been rocked by a 7.5 magnitude earthquake in the Strait of Messina followed by forty-foot tidal waves. The Messina earthquake was the most destructive in European history, with a death toll in Italy reaching according to some estimates as many as 200,000. British journalist Laurence Jerrold wrote of Paris in 1910, “I felt for a moment as if I were landing again from the boat in Messina Harbour, four days after the earthquake.” Surrounded by the flood’s devastation, with his heart pounding and mouth agape, Messina was the only event he could imagine that could help him comprehend the scene now before his eyes in Paris.

“A lamp-post or two awry,” Jerrold wrote, “the pavement upheaved, railings twisted, a quiet sheet of water covering what had been streets, and everywhere dead silence; houses dark and empty, a crowd in the distance as silent, moving slowly,” Jerrold wrote of Paris. “That was also what one first saw in Messina Harbour.... [Paris] looked as dead as the Marina at Messina.”

Parisian municipal workers from every branch of the city’s staff came to the aid of people, including the agents of Métro Line 8, who received a recommendation for special praise for their diligent work on the Left Bank. As the water began to rise, they fanned out across the area, preparing residents for what was to come. In the words of the nomination: “They immediately warned the inhabitants and businessmen of the Grenelle neighborhood and recommended that they protect their merchandise and furniture for the time being.” For days, these men returned to place after place, checking on people and making sure that everyone was safe. Several of them spent hours at a time in water at least two feet deep, collecting scraps of wood to construct rafts and walkways that could move stranded people out of harm’s way.

Sandbags holding up the quay walls outside the Louvre

Reports began to circulate that the Seine had overrun the storage facility in the basement of the Louvre and that the water-soaked quay walls were buckling and bending under the pressure of the mounting river. Alongside the former palace with its precious artifacts, the sagging roadway threatened to collapse. As soon as police arrived on the scene, they quickly shut off the streets on the side of the Louvre facing the Seine. Workmen began hauling hundreds of sandbags and dozens of shovels, the most basic tools of flood control, to the quay wall. The sound of the rushing water grew closer over the wall as several dozen engineers, soldiers, and city workers piled up sandbags, packing them tightly to reinforce the barrier. Shouts rang out to keep them coming, and row after row of bags went up, thudding into place as wet burlap met wet burlap.

Map from the official investigation showing the flooded areas in the Paris region

Paris sits at the first of six horseshoe turns in the riverbed, each looping back on itself in a 180-degree turn as the water heads downstream. Combined with the relatively mild grade from Paris to the ocean--Paris is only about 250 feet above sea level--this means that once a great volume of water reaches Paris, the land itself provides little incentive for it to move on quickly. And that volume is great, since the entire basin covers an area over 48,000 square miles, filled with streams and rivers that feed into the Seine.

Boats began floating through the streets as enterprising Parisians created ferry services across the water in neighborhoods where the only way across was by boat. Police publicly reassured residents who lived near the river that the city would row them home if necessary.

Sometimes as many as five or six people piled into a boat, launching out into a street that they normally crossed on foot. Well-dressed men in bowler hats and thick woolen overcoats frequently sat next to workmen in caps and cheap jackets. Rather than using oars, boatmen propelled their craft by plunging long poles into the water and pushing off the surface of the street below, one reason why so many commentators began comparing the situation to Venice. The pilots of these boats remain anonymous, but they were likely river workers, who would have had access to boats and knowledge of how to steer them. Passengers sometimes wondered whether this act of kindness was a form of profiteering since the police usually reimbursed the boatmen. To quell any fears of exploitation, boats piloted by police or sailors eventually replaced private boats.

One observer compared these ordinary boats to Venetian gondolas, but the Parisian “gondolier” did not sing: “How could he sing in the middle of these ruins, at night when one could hardly hear anything but the howling of dogs interspersed with cries for help?”

Despite all the damage, the beauty of Paris still shone through, especially after dark. Light from the emergency oil lamps and the few remaining electric bulbs sparkled on the Seine. The river now spread out like a vast, watery plain across parts of the city, erasing the clear distinction between Right and Left Bank. Where water on one side of the quay wall and cobblestone on the other once clearly defined the river’s edge, now the wet streets vanished and the Seine lapped against the walls of buildings.

At the Quay de Passy, a man with a cart pulled up to a small ramp at the base of a staircase where a throng of people, including women in large fashionable hats, waited their turn to be pulled through the ankle-deep water.

The wards of the Bouciaut hospital filled with water, threatening to drown hundreds of helpless patients. Police and hospital staff quickly moved to evacuate those who could not help themselves. To move each patient, a pair of rescuers grabbed the handles on each end of a cot, then shuffled carefully across the hastily constructed walkways. They carried the sick to rain-soaked wagons that in some cases were already taking on water. Very few of the vehicles had any covering to protect their passengers on the journey to safety. Coal dust or plaster, left behind from the normal uses of these donated vehicles, coated many of the improvised ambulances.

Depiction of a Red Cross shelter

Thousands of suddenly homeless Parisians rushed into shelters around the city set up by Red Cross workers, the Catholic church, and the government. As the poet Guillaume Apollinaire approached the shelter at the Church of Saint-Sulpice, a well-dressed woman arrived at the same moment with tears rolling down her cheeks. “I don't have a home anymore,” she cried, “and the city hall sent me here.” She and Apollinaire entered the seminary doors to find hundreds of others in the very same situation already under its roof, now calling the church home.

Political leaders touring the damage

Politicians and city leaders, including the president, prime minister, and police chief, visited the victims to show their sympathy and quickly began passing legislation to authorize millions of francs worth of loans, grants, and assistance. They had to do their work in the dim light of old fashioned oil lamps once the power in the National Assembly building went out. Paris City Council President Ernest Caron stood before the members and lauded the fact that “everyone had played a role in the good work; every citizen, every association, every group, each part of the administration, civilian and military, everyone has fought with zeal and courage. Every social and political difference has disappeared and blended, in the same spirit, towards those who are cold, toward those who are hungry.” Everyone in the chamber shouted back in agreement: “Très bien! Très bien!”

On a visit to the suburban town of Charenton just east of Paris, police chief Louis Lépine guided the president and his party around the flooded area, pointing his cane in the air to show the course of the water’s progress. “Do you think,” President Armand Fallières asked Lépine, “that the damage is worse here or in Paris?” Much worse in places like Charenton, Lépine asserted. Paris had the men, boats, and tools, he said, that were sadly lacking in the suburbs. “Poor people live in this area, and they have neither shelter nor resources.” As Lépine and the president slogged through the mud, they heard cries for help coming from an upper floor of a building surrounded by water. “So horrible!” the president exclaimed, and asked people to go to the aid of the person in need. Lépine ordered his men to hurry, and the agents ran off to find the shouting flood victim. As the president and Lépine were returning to the car, they heard other voices crying out, “Don't forget us! Help us!”

Some people attempting to escape on their own grabbed pieces of wood or debris and fashioned makeshift rafts. But as they rowed, those trying to flee often struggled to stay above the water’s level. Newspapers reported drownings when people tried to travel through the high water in the city streets. When a dockworker tried to help a woman through a flooded area at Porte de la Gare, they both slipped and fell into a sinkhole. He was able to grab onto a tree, but she vanished into the water.

Parisians constructed passerelles, or wooden walkways, to continue moving throughout the city during the flood. Along with boats, these walkways became one of the most important ways of getting around the city.

After wading through the mud, Robert Capelle traced the edge of the riverbank in the dark by holding onto the ropes that cordoned off the Seine. When Capelle and his friends arrived at Rue de Beaune, they still could not find dry land, but instead mounted “une passerelle established on platforms about two meters above the ground. 150 meters long; one meter wide; vision obscured or blinded by the acetylene lamps. I arrived at Rue du Pré-aux-Clercs; all five of us still had dry feet to take us home.” Capelle was relieved that his day was finally over. “I had never heard anyone say with the same emphasis the simple words ‘at home.’ The challenge made being ‘at home’ feel like such a prize.”

The flood created a strange kind of intimacy. Police and soldiers showed up unannounced at a stranger’s door with supplies. Occupants of a rescue boat or a shelter suddenly became neighbors, and maybe great friends. Men carried women across a flooded stretch of water, bringing into contact bodies that would ordinarily never touch so directly--a soldier and a proper middle class woman, a servant and his wealthy mistress. Men carried other men on their backs. People handed their children off to complete strangers, if only for a few minutes so that they could reach safety. Often there was no other choice. The work of rescue required bending some of the social boundaries that kept many Parisians separated by status or occupation.

The cover of the popular, cheap magazine, Le Petit Journal showed a figure blending both Sainte Geneviève, the patron saint of Paris, and Marianne, the symbol of the French nation, joining with Parisians in acts of charity and rescue. Above her head is the motto of Paris: Fluctuat nec murgitur, “She is tossed about by the waves, but does not sink.” It argued that all of Paris and France came together to rescue the capital from the horrors of the flood.

Illustration from Le Petit Journal

But there were also signs of discord and tension during the flood. Looters broke into abandoned homes, stealing for survival or opportunity. Angry crowds exacted vigilante justice on the thieves, sometimes tying them to telephone poles or lynching them. Scattered gunfights broke out, especially in the hard-hit suburban towns, and police closed off vulnerable neighborhoods, especially those where malfunctioning streetlights left the area in the total darkness of the long, winter nights.

Animals at the Paris zoo were helpless as the water seeped into their habitats. Zookeepers rescued most, but a few perished.

The central hall of the Gare d’Orsay, the train station opened only ten years earlier, now sat feet under water. The electrical tracks which made it the city’s most modern station were useless. Many photographers concentrated their lenses on the enormous arched window, which allowed light into the dark and empty space of what would normally have been the bustling platform area, but now was a motionless lake. The illuminated archway is reflected in the still water, creating a stunning symmetrical image. Although the water is stagnant and foul, the reflection makes the Orsay look like a beautiful ancient temple sitting in ruins.

Postcard sellers weaved through the crowds along the sidewalks by the river, holding up handfuls of images for all to see and buy. Despite the suffering, many people wanted to remember the dramatic events now that they seemed to be over, and postcards were a cheap and easy way to do so. As early as the 23rd, one American witnessing the rise of the Seine remembered: “When we reached the Rue Félicien David and actually saw people in boats, we bought photographs from an enterprising hawker, wanting to preserve this souvenir of Paris.” Dozens of photographers had been combing the city streets during the days of high water, capturing the struggle and triumph in the human drama that unfolded in front of their lenses. And they were now selling those photos back to the residents who had lived through the experience. Vendors offered these mementos either individually or in small booklets with perforated edges so that cards could be easily detached.

Map of flood damage within Paris, including areas inundated with water moved through the subway system.

When the water entered a subway tunnel under construction near the Gare d’Orsay, it flowed back underneath the river’s main channel, and shot above ground in Right Bank neighborhoods where no one expected it to reach. The city’s own infrastructure made the situation worse.

One journalist remarked on the irony of a nation that had mastered the air through flight--France was a leader in developing aviation technology and by 1910 boasted the beginnings of a significant airplane industry--now losing its battle to control water. “It’s the revenge of nature: the water has avenged the air. We leave this affair a bit wet and very humiliated.”

The damage to the city was enormous, totaling some 400 million francs, or 1.4 billion euros as of 2010. Sewers overflowed, telephone and telegraph lines were cut, electricity and gas failed throughout the city thrusting people into the dark. Fortunately, most Parisians still used wood and coal for heat.

Barrels floating in a wine warehouse near Bercy.

The Seine poured into wine storage facilities pushing dozens of barrels into the main river channel and propelling many of them downstream. Frightened merchants yanked on rubber waders and slogged through waist-high water trying to wrestle the enormous casks back into their warehouses. After only brief soak in muddy water, much of the city’s precious wine supply—not a luxury, but a staple of life—began to spoil.

From Le Petit Journal Illustré

Damage was particularly bad in the suburban towns upstream and downstream from the city. One public hygiene expert described the conditions in Clichy. The Seine, he wrote, “has left on the bank a considerable deposit of household waste and mud along a stretch of at least 700 meters. This waste is beginning to putrefy and is giving off an already annoying odor which will soon be intolerable.”

Once the water began receding on January 29, Parisians who had been trapped in their homes or shelters came out into the streets to celebrate. Pointing at the Seine, they said to one another, “It’s going down, it’s going down. Ah! It’s not soon enough.” Cleaning the city would go on for weeks and months after the water began to fall. Steam pumps roared around the city removing water from basements. Inspectors made sure that Parisians properly disinfected their basements before moving back home. But the police chief banned throwing confetti during Mardi Gras, despite the city’s normally substantial celebration. The clogged drains and sewers could stand no more debris.

The water rose again in November 1910 causing Parisians to fear another great flood. The Seine did not climb nearly as high as it had the previous January, but the city watched and waited anxiously.

One of the few flood markers around the city is at 18 rue Bellechasse.

Beginning in 1911, the city installed plaques and markers along the river and on various buildings showing the level of the water during the flood, most of which survive today. But there were no other lasting attempts to indicate how high the river had gone, and most Parisians and visitors either ignore these rather inconspicuous marks or simply have no idea of what they mean.